Southern Comfort (playing through October 29th at CAP 21 Theatre Company) is a new musical adaption of Kate Davis’ award-winning 2001 documentary about the life and death of Robert Eads, a transgender man living in rural Georgia. This polished and nuanced production has the relaxed and comfortable feel of an off-Broadway hit enjoying a long run; the ensemble cast, lead by Annette O’Toole in a striking performance as Eads, creates a world that feels authentic, lived-in and familiar.

The musical (like the documentary) follows Eads in the last year of his life, from Easter through the following winter. Eads, diagnosed with ovarian cancer, found it difficult to find proper medical treatment, as doctors and hospitals claimed their other patients would be made uncomfortable by his presence.

Although the gradual progress of Eads’ illness provides the underlying tension, the musical does not wallow in sentimentality or anger. Instead, the smart and understated book and lyrics by Dan Collins chronicle the close-knit community of individuals surrounding Eads, detailing their family rituals and traditions in tiny Toccoa, Georgia. Robert sings in the opening sequence of a backyard Easter celebration:

Family’s an iceberg we ride into the sea

The parts that break away we gotta lose.

But it could melt entirely and I know I’ll still be

Kept above the water by the family I choose.

|

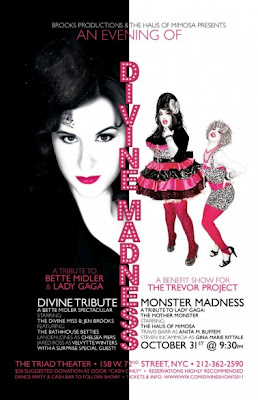

Jeff McCarthy (as Lola Cola, left)

and Annette O'Toole (as Robert Eads)

Photo by Matthew Murphy |

At the Easter gathering, Robert has invited his new girlfriend, Lola Cola, to meet his “chosen family”, who gather every Sunday: transman Cas and his wife, Stephanie (Todd Cerveris and Robin Skye); and Maxwell, a young transman (the impish Jeffrey Kuhn) who has a sometimes-testy father-and-son relationship with Robert. Lola (played by Urinetown’s Jeff McCarthy, in a sharp performance which evokes a mixture of Allison Janney and Anjelica Huston with a basso Kathleen Turner voice), is less comfortable in her own skin than the others. In one of the standout songs of the evening, “Bird”, Lola sings of her desire to escape her masculine frame and deep voice, as she strips away her women’s attire to resume her everyday male identity, John, proprietor of a heating-and-cooling repair shop.

In the song, McCarthy duets with a member of the band, Lizzie Hagstedt (also playing bass), whose pure soprano is what Lola wishes her own voice could be. Hagstedt and three other actor-musicians (Allison Briner on percussion, David M. Lutken on guitar and Joel Waggoner on violin) function as singing storytellers, occasionally stepping into the story in the roles of outsiders (primarily medical personnel and estranged parents – including standout work from Briner and Lutken as Eads’ mother and father, who stubbornly call him by his birth name, Barbara.) Astonishingly, they all play the score from memory (led by music director and pianist Emily Otto.)

As time passes, Lola becomes part of the circle, while Maxwell finds a girlfriend of his own, transwoman Cori. As the group prepares to attend Southern Comfort, the annual Atlanta transgender conference, conflict arises between Robert and Maxwell over the younger man’s decision to pursue phalloplasty – what the characters refer to as “the bottom surgery.” The script delves into the conflicting opinions surrounding the procedure without becoming didactic.

ROBERT: This is crazy. We always agreed that man or woman was about what’s in your heart and your head, not between your legs.

MAXWELL: Then why’d we start takin’ testosterone? Why’d we get the top surgery?

ROBERT: That’s just about bein’ able to function out in the open as who we are without gettin’ ourselves killed. We gotta pass.

MAXWELL: Well, I want to pass more.

ROBERT: So what does that make me?

MAXWELL: Ain’t about you, it’s about me.

ROBERT: Like Hell it ain’t about me. You think what’s happenin’ to me – my cancer – is just Barbara eatin’ me up inside cuz I ain’t real.

Being ‘real’ and what that means is one of the central themes of the story: in the CAP21 space, the audience surrounds the stage – throughout the evening, you are aware of watching the audience watch the performers. This awareness adds an extra layer of tension to the performance – underlining the constant stress the characters are under to “pass.” Unlike some film-to-stage adaptations, the piece reveals itself to be innately theatrical because it is so much about the actors’ performance of gender, in every variation. This aspect of the show is distilled in the joyous and energetic second act song “Walk the Walk”, when Cori (a luminous Natalie Joy Johnson) leads a seminar on ‘Sensual Feminine Movement’ at Southern Comfort:

Cuz a girl ain’t what she’s wearin’

And a boy ain’t how he’s born.

You’re the moves you make n’ they gotta take you

Past the things you’ve worn

Cuz what a body is or not

Is just a whole lot a’ talk

You gotta walk the walk.

|

Annette O'Toole (as Robert Eads)

Photo by Matthew Murphy |

The cast’s work is subtle, detailed and completely believable. Annette O’Toole, perhaps most widely known for her role as Martha Kent on Smallville, throws herself into the role of Robert Eads in a fearless and full-bodied performance. Her voice, throaty and clear, is well-suited to composer Julianne Wick Davis’ folk and bluegrass score. Davis, also responsible for orchestration, builds interesting instrumental textures, and sensuous, layered vocal harmonies. The music is at times restrained, at times soaring, finding rhythmic complexity in the folk idiom. Occasionally the density of the text setting makes lyrics difficult to catch on first hearing, but the joy of hearing natural, unforced and unmiked voices in the intimate space is worth losing a word or two here and there. Davis makes clever use of vocal ranges, often placing male and female voices in unison.

|

Robin Skye (as Stephanie, left)

and Todd Cerveris (as Cass)

Photo by Matthew Murphy |

The costumes, by Patricia E. Doherty, instantly define character in their bulls-eye specificity, from Robert’s western-cut leather jacket with bolo tie to Lola’s Talbot’s-pantsuit ensembles; the warmly humorous Robin Skye as Stephanie wears Wal-mart pharmacy eyeglass frames exactly right for a particular type of Southern trailer-park gal whose culinary specialty is Snickers salad (“Snickers, green apples, cool whip and vanilla puddin’. Secrets in the puddin’. It’s gotta be instant!”) The hair and wig design by David Brian Brown, along with April Schuller’s makeup design, bring the characters to fully realized life, while never veering into Southern-eccentric caricature. The hair and makeup work comes into play in one small but moving moment when Cas (the low-key and affecting Todd Cerveris) shaves off his beard, as he prepares to visit the family who only know him as their daughter Debbie.

The set, by James J. Fenton, transforms the small CAP21 black box into Robert’s weathered porch and backyard. Shelves illuminated by small sconces filled with curios and bric-a-brac line the walls: closer inspection reveals that the objects are totems of masculinity and femininity (a toy truck, a ‘Skipper’ doll carrying case, a tobacco can.) In one subtle effect, the sconces light up during Robert’s song about his childhood, “Barbara”, illuminating actual photos of Robert Eads as a young girl. (Careful observers will also spot a small photo of Eads as you enter the theater.)

The beautifully textured lighting design, by Ed McCarthy, manages to depict not only the Georgia sun in every seasonal variation from summer to winter, but also the unforgiving harshness of blue-white hospital lights for several crucial sequences.

Thomas Caruso’s fluid direction nimbly handles the script’s shifts from naturalistic scenes to documentary-style direct address, to the more abstract moments when the musicians enter the story as peripheral characters. The pace is leisurely at times, but does not drag: Caruso trusts that the small, nuanced moments of the story will hold our interest (which they do), and does not try to rush the story unduly.

Southern Comfort is also very funny: bookwriter Collins deftly punctuates the script with sly humor that feels true to the characters. The script handles the more emotional moments skillfully, never descending into oversentimentality or cliché. The show stealthily builds to an emotional climax: a substantial percentage of the audience was reaching for tissues to dab at suddenly-moist eyes. The message of Southern Comfort is universal and simple:

Down with living your life under there.

Up with spring.

Oh, spring up everywhere.

With Southern Comfort, CAP21 continues their tradition of presenting intelligent and moving new musicals. One hopes that this production will find the backing it needs to make the transition to an open-ended run. This is a powerful evening.

Southern Comfort runs through October 29 at the CAP21 Black Box Theater, 18 West 18th Street. Show times are Wednesday-Saturday at 7 PM.